TRAM - Term Rewriting Abstract Machine

TRAM (Term Rewriting Abstract Machine) is an implementation of term rewriting systems. There are a few versions named TRAM.1, etcetera, in which different design choices have been made.

We use the notation TRAM (all caps) to refer to the implementation, the abstract machine, or the rewrite engine, and we use the notation Tram (lowercase) to refer to the input language of such systems.

Tram supports left-linear unconditional term rewriting systems. TRAM is created in the spirit of

Tram is available at Github

Design Criteria

In Section Term Rewriting, we discussed criteria that make term rewriting a suitable basis for general programming and specification. Term rewriting systems offer a minimalistic, powerful, unopinionated framework for the design, specification, and implementation of software:

- Unopinionated

There are no built-in numbers, strings, arrays, objects, etcetera. This is bad if you want a flying start; use Python in this case. It is good if you want to be precise and use TRSs both as a specification and an implementation language. - Minimalistic

In this section we discuss minimal magic: term rewriting systems can be explained without any significant assumptions or tacit knowledge. - Powerful

Powerful is a subjective and contextual term. Here we take it to mean “capable of specifying or implementing complex structures and mechanisms”.

The design criteria for TRAM follow:

- Small and easy to understand in minutes

TRAM.1 is small (~650 lines of standard C code using a few standard libraries. One reason to make TRAM light-weight is the underlying goal to implement TRAM directly on FPGA hardware - Reasonably efficient

TRAM is reasonably efficient (e.g., significantly more efficient than a naive recursive implementation).- The absence of assignment in pure term rewriting means that the language is side-effect free, and terms are never altered. Consequently, a single-pass garbage collector suffices

- TRAM represents terms using nodes with fixed arity (2). Consequently, a non-compacting garbage collector suffices

- TRAM can use a so-called ‘bytecode engine’, assigning part of the work to the compiler. This approach is foreseen in TRAM.3

- TRAM uses an innermost reduction strategy which means that only terms are built which are in normal form

- Capable and self-contained TRAM.1 is a stand-alone tool suitable for batch processing

Notes:

- At the time of writing, TRAM is implemented using 32-bit words.

- Many conceivable extensions might make TRAM more practical, such as integers, floats, external functions, etcetera. But TRAM is implemented from the tenet that TRSs offer an expressive general-purpose framework that, with the exception of high-speed or memory-intensive applications, is truly sufficient. Accordingly, TRAM is created with a very low degree of magic.

Extensions

Several extensions/adaptations can be named which may be added to TRAM at some point, such as

- direct memory stacks instead of stacks-as-terms

- indexes to speed up execution

Tram is intended to be minimalistic, and many extensions can be added as source-to-source transformations. For example:

- Nonlinear left-hand sides

- Other conditional rewrite rules

A few features could have been handled this way but are deemed crucial to the development effort:

- Tram has comments in order to make source code self-documented

- In Tram, rewrite rules are written as

lhs = rhs;. Strictly speaking, the meta-notation of terms defines the symbolsrlandeorto represent lists of term (rl(lhs1,rhs1, rl(lhs2, rhs2, ..., eos)..)). However, that meta-notation is difficult if not impossible to maintain by humans. Also, the implementation uses a more compact and more efficient model to store rules.

Strategy

Before diving into TRAM, we first set the stage.

A term rewriting system (TRS) is an ordered set of rewrite rules. Given a strategy and a subject term, term rewriting is an iterative process in which a sub-term of the subject-term and a rule are identified, such that the left-hand side of the rule matches that sub-term. Then, that sub-term is replaced by the corresponding instance of the rule’s right-hand side. This iteration is repeated until no more reducible sub-terms can be found and the resulting subject term is in normal form. If the TRS is confluent and terminating, this process leads to a unique normal form; otherwise, the result may be non-deterministic or the iteration may never terminate, which may be a bug but might also have sensible applications.

As described in Section Term Rewriting, we limit ourselves to two aspects of strategy: choosing a sub-term and choosing a rule to be considered. Two options were mentioned for each choice: innermost and outermost strategies, and textual order, and/or specificity order.

Outermost strategies are somewhat better behaved with respect to termination, but there is an overhead: terms are built which are not normal forms. That is a waste of resources. As we will see, in an innermost strategy, only normal forms are built; all other function symbols remain on a stack (which has less overhead in principle). For the moment, we consider innermost reduction only.

Secondly, textual order can be applied such that it coincides mostly (though not always) with specificity order. In addition, textual order coincides with common programmers’ experience. For the moment, we consider textual order (though we will revisit this choice).

Memory Management

Section Memory Management offers an introduction and rationale of TRAM’s memory management and garbage collection. Section Term Rewriting offers an introduction and theoretical foundation of the concepts of symbols, variables, terms, rules, matching, instantiation, etcetera.

TRAM distinguishes three data types: symbols, variables, and compound terms. Symbols and variables are represented as numbers (32-bit ints in TRAM.1).

Nodes

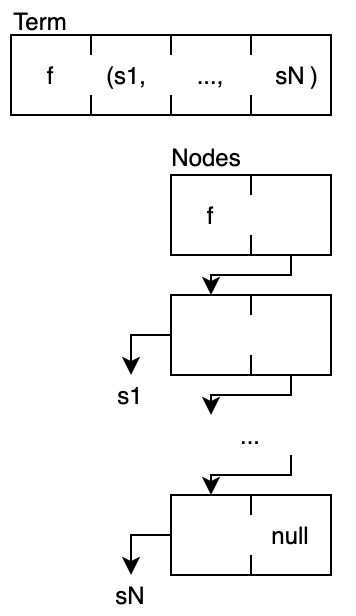

TRAM terms are represented with nodes. A node is a structure with three fields called car, cdr, and nxt. Nxt is used for memory management and will be discussed elsewhere. The fields car and cdr hold a value, which is a symbol, a variable, or a reference to another node.

The transformation of terms with arbitrary arity (number of arguments) to binary tree structures happens in TRAM parsers. TRAM engines are only concerned with binary nodes.

An entire term is represented as a set of linked C structs. The term is represented as a value by storing a reference to the root struct of that term. This reference is direct (TRAM doesn’t need or use handles). Since TRAM.1 uses 32-bit numbers, a reference can’t be a pointer, so an offset is stored. A reference to a term is a 32-bit index in the array of all nodes.

Values

To summarize, values are 32-bit ints which represent

- symbols

- variables

- nodes (a reference to the root node of a term)

Stacks

A term rewriting implementation uses stacks for

- The parser. Terms use parentheses, which implies that a scanner is insufficient and a parser is required, which must use a stack. Strictly speaking, push-down automata could also be used. At this point in time, that idea hasn’t yet been applied.

- Intermediate results. As mentioned, an innermost strategy refrains from building terms until they are known to be normal forms. But the outermost function symbols that have yet to be matched must be stored somewhere, and (as mentioned) a stack is appropriate.

- Recursion. As mentioned, the highly recursive nature of the meta-interpreter has been implemented with iteration, but that iterative process still needs storage, which is stack-like.

- Finally, to produce output, the engine needs a stack while printing terms.

To simplify TRAM, these stacks can be implemented using TRAM’s own memory manager (i.e., nodes). This approach is simple but inefficient.