Virtual Memory

In the early days of computing, memory was expensive and small. Programmers had to write small programs that used as little memory as possible. Larger programs were decomposed in overlays. For instance, each phase in a compiler wrote its results to a file, after which the next phase could be loaded (overlaying the previous) in memory.

As memory grew, the demands also grew, so programmers were spending significant time on this manual memory management. A model was engineered which solved this: Virtual Memory.

Conceptually, virtual memory means a program can use a lot more memory than is (physically) available. That virtual memory is simply stored on disk, and physical memory is used as a cache for the memory stored on disk (very much as a CPU cache temporarily stores memory content). Note that this is the same as a program storing intermediate results in a file, with one exception: the operating system must handle the virtual memory administration automatically.

Paging

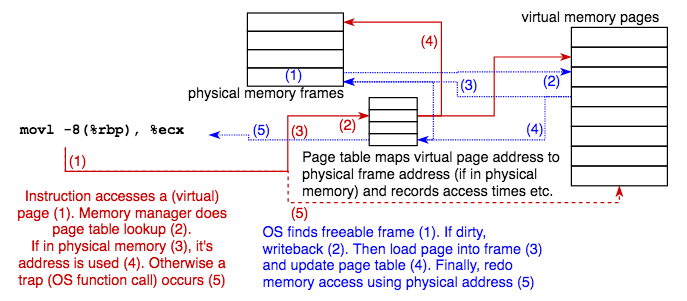

The heart of virtual memory is paging. The entire memory a program uses is divided in pages. Whenever the program accesses a page which isn’t currently stored in physical memory (this is called a page fault), that page is loaded into a section of memory of equal size, called a frame. When no unused frame is available (memory is full), the OS looks for a frame it can recycle, for instance a frame which hasn’t been used for some time (the OS remembers last access times for all frames). If that frame is dirty it is first written back to disk. Then the page the program wanted to access is loaded into the now unused frame, and memory access can finally take place.

Alarm bells might ring: for every memory access we access a table, which is also stored in memory. Won’t This Fail?

Good question. We already know part of the answer: page tables are accessed so frequently that they are usually cached.

The second part is that some specific hardware, called the MMU (Memory Management Unit), is responsible for the computations.

Thirdly, if the CPU (or rather a core) needs to wait a moment, a second logical core quickly takes over to avoid waiting (multithreading).

Memory Management Unit, Translation Lookaside Buffer

An MMU is a dedicated piece of hardware (today embedded in the CPU) which controls all memory access (so it’s located between the cores and the address bus), either before or after the caches.

Before looking into the Page Table, the MMU may look into an associative cache: a content-addressed lookup table called the translation lookaside buffer (TLB) which holds recently used pages. A TLB hit results in a physical address which can be used immediately. Only on a TLB miss will the page tables be traversed (there can be multiple levels).

The MMU generates a trap (i.e. invokes the OS) if a page isn’t yet loaded in memory or if any error condition occurs =>

Page Table Entry

A page table entry (there’s one per virtual memory page) holds the virtual and physical (if loaded) page addresses and various control information:

- a dirty bit

- an R/W bit (allows pages to be R/O)

- a bit indicating the required permission level (user or system)

If the virtual address points outside virtual memory, or if R/O or access rights are violated, the MMU generates a trap which invokes an error handler in the OS.

Segmentation

Segmentation stems from the time of overlays: instead of using a single contiguous memory space, a program divides its memory in separate segments, each holding code or data belonging to different aspects of the program. Segmentation is used for virtual memory, where segments are loaded and stored as the need arises, but it is also used as a programming structuring mechanism.

The main difference between paging and segmentation is that paging is automatic but segmentation is under program control. Note that segmentation and paging can be used together.

Segmentation is still being used today, and one of the most dreaded error messages when programming in C is ‘segmentation fault, core dumped’: indicating a memory access violation.

Page Size

There is no ideal page size: too small and the administration overhead becomes noticeable; too large and waste and performance loss might result.

The ARM MMU (included in all modern ARM processors) offers four sizes: 4k / 64k for two-level paging suitable for computers and phones (we’ll discuss multi-level paging in a moment), or 1M / 16M for one-level paging more suitable for embedded multi-media systems.

The x86-64 MMU usually sticks to 4k pages, but does support larger ‘hugepages’.

x86-64 Paging

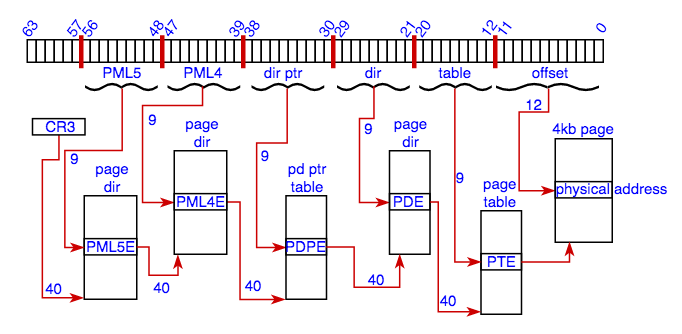

Today, most Intel processors offer 4-level paging, but this architecture is limited to 256 TiB, so this Intel whitepaper https://software.intel.com/sites/default/files/managed/2b/80/5-level_paging_white_paper.pdf sketches the next gen 5-level architecture, good for 128 PiB.

This mode uses 57 bit addresses =>

Note: Whereas metric kilo, mega, giga, tera and peta count in powers of 1000, tera being 1000^4, the ISO and IEC promulgated standard counts in powers of 1024: kibi, mebi, gibi, tebi and pebi, a pebibyte being 1024^5 bytes, so 128PiB=1.4e17 B

x86-64 Five-level Paging

- lower 12 bits are the offset in the physical page (2^12=4k)

- other layers use 9 bits = 512 entries (2^9=512) of 64 bits. A 40-bit base pointer and control various bits

- the base of the page-table tree is pointed to by register CR3

- each process has its own CR3 register which cannot simply be changed, thus every process is limited to its own memory

- in a virtualisation environment the higher levels are owned by the guest, but the lower levels are owned by the host. This way, guest memory management is as fast as host memory management