Language Processing

Assembler

A CPU fetches bits from memory and decodes and executes them, which means that bits are altered here and there. All a CPU sees are bits – numbers. People aren’t too good at numbers. Programming a computer using bits or even hexadecimal would be disastrously complex.

The programming language of the ISA is called Assembly Language, and the tool that translates Assembly to bits is called an assembler.

Unlike other languages, assembly doesn’t offer abstractions such as control structures (if, while) or data structures (arrays, structs).

Assembler offers

- the use of labels instead of addresses. A label can be used to jump (i.e. goto) a place or to store data

- the use of opcodes as a mnemonic for instructions

- pseudo-opcodes which do not lead to instructions but rather direct the assembler

- a somewhat mnemonic notation for addressing modes.

We could look into manuals and tutorials to study assembly, but there is a much more effective way: study it on your own computer. The GNU C compiler offers all one needs.

The GNU C compiler

Every Linux machine, VM or Mac either has gcc installed, or it’s easy to do so.

Gcc compiles C to executable, but can also produce assembly language code.

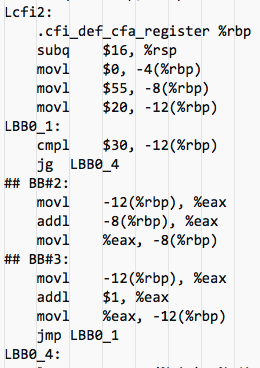

For the following example, we’ve compiled a small program. We’ve chosen weird numbers in order to recognize the resulting assembly code. This program is compiled using gcc -S asmtst.c (telling the Gnu C compiler to stop after producing an assembly code file), which produces the file asmtst.s. This was done on a Mac with an Intel processor.

| |

Assembly

- Labels are at the beginning of a line followed by a colon. They are used for jump-to (jmp) or jump-on-greater (jg).

- Most lines have the form

opc oprndwhereopcis an opcode: the name of an ISA instruction, andoprndare the zero or more operands that instruction requires. %rbpis the frame pointer; local variables are indexed off that pointer- So

movl $55, -8(%rbp)is a long move of the decimal value 55 into the local variableswhich ’lives’ 8 bytes below the frame pointer (%rbp) - A macro mechanism where a set of instructions can be given a name, such that using the name will lead to those instructions being inserted.

cmpl $30, -12(%rbp)jg LBB0_4comparesi(located 12 bytes below the frame pointer) with 30 and jumps (i.e. exits the loop) if it is greater.- Note that by using labels we avoid having to count the number of instruction bytes. The assembler translates the label to an appropriate offset.

- The C language statement

s += i;translates to three instructions:iis put in the general purpose registereax, thensis added to it, and then the result is stored ins.

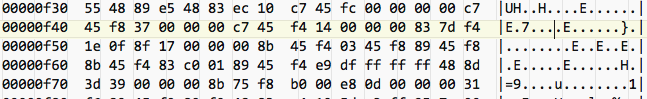

Machine Language

Below is a snippet of the machine code taken from the executable of this program. The use of numbers such as 55, allows us to quickly determine the location of this snippet.

Using the knowledge we now have, we can already interpret this snippet to some degree.

Exercise:

if I tell you c7 45 is movl, can you tell me if this machine is little endian or big endian?

⊙

Exercises (click for solutions!)

The values at address 0f42…0f45 are 37 00 00 00. 37 hex = 55 decimal, so the least significant byte occurs first, so this machine is little-endian.

Lower & Higher Level Languages

Assembly is called low-level because it doesn’t offer any abstraction mechanisms beyond labels, opcodes and macros.

The programming language C, regarded by some as a generic assembler, at least offers named functions, control structures and data types.

Java, C#, JavaScript and Python offer Object Orientation, a complex scala of parameterized data types, name spaces, and much much more.

So, lower vs higher is a relevant distinction, but most languages are in fact high-level.

Functional vs Imperative Languages

All languages mentioned so far are imperative: statements (assignments) change an existing state.

One may wonder how a program could achieve anything without changing the state, but consider this Javascript statement:

console.log(55 + function f(x) { return x<=30 ? x+f(x+1) : 0; } (20));

Not a single assignment in sight. It just defines and calls a function. It does exactly the same as the C program shown earlier (feel free to test it in a browser).

A functional language is a language which isn’t imperative. Javascript is both functional and imperative.

Is There Something Wrong With Imperative Languages?

Mutability is a source of bugs. Consider this snippet of code

X=<someDataStructure>; Y=X;

# This doesn't copy the data structure but rather Y points to the same structure

# Any change in the data structure Y also changes X. This can lead to very subtle bugs

In 1998 Ericsson announced the AXD301 telephone switch,

containing over a million lines of Erlang, and reported to achieve a high availability of nine “9"s (source: wikipedia).

That’s 99.9999999% uptime, less than 4 seconds per year of downtime!

One key reason: immutability. Erlang data structures can not be changed.

There is no other language in the world that is as reliable as Erlang (and derived languages such as Elixir).

Compilation

An assembler translates assembly into object code: a sequence of numbers. Such a process is called compilation. The C compiler compiles a program either into assembly or directly into object code. In general, compilation is the process of translating one (computer) language into another.

Source-to-ISA Compilation Phases

- Lexical Analysis. Combining character sequences into logical units called tokens: identifier, keyword, operator, etc.

- Syntax Analysis. Determining the grammatical structure of token-sequences into an ‘abstract syntax tree’ structure which reflects the containment hierarchy

- Semantic Analysis. Applying semantic aspects such as variable-scope.

- Intermediate Code Generation. Generate executable code for some abstract machine such as a VM (see below).

- Code Optimization. Apply heuristics (rules of thumb). For instance, mv $X,($A) followed by mv ($A),$X stores a value and immediately fetches it. The second instruction is superfluous.

- Code Generation. Finally, generate actual ISA instructions.

- Symbol Table. All identifiers needed

Compilation, and what’s wrong with it

The main disadvantage of compilation is portability. In order to work on a platform, the compiler must be implemented specifically for that platform (not only the ISA, of which there are a few hands full, but also the OS, of which there are many).

For C this needs to be done anyway: most OSs are written in C.

For other languages this development would be prohibitively expensive.

Compilation and Virtual Machines

The common solution to the problem of portability of compiled code is “Virtual Machines”. This is a concept similar to using an ISA to provide a standard “virtual processor” which is implemented on different platforms by different microarchitectures.

Such a “Virtual Machine” will provide a standard target for a language, or a group of languages, somewhat similar to an ISA but also offering many ‘higher level’ aspects, such as object orientation, data structures, memory management and so on.

Now portability has been separated from language development; the higher level language compiler translates to the standard language for the virtual machine. This means that porting the language(s) to a different platform only requires implementing the Virtual Machine on that platform; once that is done, any and all languages which are made for that Virtual Machine will work on the new platform.

The language compiler itself is often written in its own language, so once the Virtual Machine has been implemented on a new platform, the compiler will then work on that platform as well.

The Virtual Machine is generally written in C and requires only mild adaptations to any new platform, so porting the VM is usually straightforward.

Some Common Virtual Machines

Note that these virtual machines are entirely different from the VMs used to run, say, Linux on a Windows machine

- .Net CLR: One of the many reasons why the .Net platform is successful is that it is built around a well-documented virtual machine which is used as the target for tens if not hundreds of languages including Java and C#.

- JVM: the Java Virtual Machine today is also well documented and supports many source languages

- Beam: the Erlang virtual machine, supports a handful of languages aimed at its specific conceptual model

- Python Virtual Machine: supports mostly Python and derivatives

Interpretation

Once a compiler has translated a source program into the ‘machine language’ of a virtual machine, there are two ways to proceed.

One way is further compilation: on most platforms, .Net “Common Language Runtime” (CLR) code is compiled down to ISA machine code. The beauty is that CLR code can be distributed and all platform specifics are dealt with below that level.

Another way is Interpretation. Just as the µarchitecture fetches, decodes and executes ISA instructions, so can we write a program that fetches, decodes and executes, say, JVM instructions.

An interpreter is a program that interprets instructions in some language one by one, and mimics their effect on the machine state.

Bytecode

Few languages are interpreted at the source code level, because that would mean that the analysis of the source text (syntax, grammar, validation) would have to be done repeatedly. If the source language is high-level, any sensible interpreter would first analyze the source text and translate it to some intermediate language, suited for direct interpretation.

In practice, any such intermediate language is modeled as a virtual machine. Since the instructions of this machine are commonly represented as numbers, or bytes, (just as ISA instruction), the language for such a machine is often called bytecode.

Reverse Polish Notation (RPN)

How much is (((5-3)*(7+1)-(6-4)*(4-3))+((5-2)*(2-5)+(6-3)*(4-2)))?

How would one generate ISA-level code that computes this? One approach would be to assign different registers to each pair of parentheses: mv $5,Rx; sub Rx,3, and so on.

However, this is wasteful of registers and doesn’t scale for more complex computations.

Reverse Polish Notation (RPN) is mathematics, but it plays an important role in compilers and abstract machines (and a few other areas).

In RPN, the operator is written behind the arguments instead of in between. Not 5*6 but 5 6 *.

Suddenly, parentheses are no longer needed!

(((5-3)*(7+1)-(6-4)*(4-3))+((5-2)*(2-5)+(6-3)*(4-2))) becomes

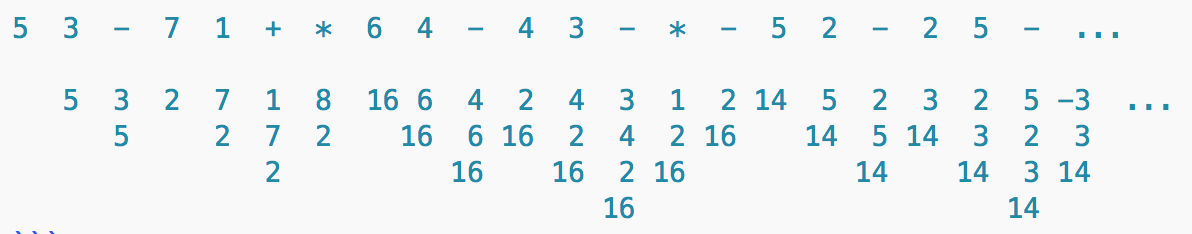

5 3 - 7 1 + * 6 4 - 4 3 - * - 5 2 - 2 5 - * 6 3 - 4 2 - * + +

It’s different, but is it better?

To compute RPN we need a stack (to hold the data, operands and intermediate results). To compute an expression: from left to right, each number is pushed onto the stack, and for each operator, the operands are popped off the stack and (very important) the result is pushed back onto the stack.

Here, below every item the content of the stack is shown when that item is processed

5 3 - 7 1 + * 6 4 - 4 3 - * - 5 2 - 2 5 - ...

5 3 2 7 1 8 16 6 4 2 4 3 1 2 14 5 2 3 2 5 -3 ...

5 2 7 2 16 6 16 2 4 2 16 14 5 14 3 2 3

2 16 16 2 16 14 14 3 14

16 14

RPN can handle arbitrarily complex expressions. It can be optimized by using registers to make it faster than simply using the memory-based stack. Interesting note: in the earlier phases, compilers often use RPN!

Some languages are built entirely around RPN. Today, one notable example is PDF. If you open the contents of a pdf document as a text-file, you’ll see lots of encoded data, but also snippets written in the RPN-based PDF programming language.

Language Processing

Most modern language processing systems consist of something like the following phases:

compile compile

source =======> intermediate =======> bytecode

bytecode: interpreted by VM

or

compile compile

bytecode =======> C/assembler =======> ISA: interpreted by µArch

Linking

Libraries are an important tool in software development because they allow us to leverage earlier work. When compiling a program that uses libraries it wouldn’t be sensible to have to compile the entire library again. But that poses a problem: when we call a function in the library, we must know its address. Where is that?

Running code using statically linked libraries requires an initial step: linking. The unlinked code of the program and all libraries are loaded together with their symbol tables. Now the address of every module is known so if module A calls function F in module B, the reference in module A’s symbol table can be replaced with the actual address of F in B.

Today, we also use dynamically linked libraries. They are called using a slightly different mechanism which allows the OS to link them when the code is already running. There is a slight overhead.

JIT

Compilation takes time. For some languages, linked libraries are appropriate. However in some other circumstances, another principle is used: just-in-time compilation (JIT). The library isn’t compiled, and maybe not even loaded until it is actually used. More likely, the libraries are compiled to bytecode, but the second phase (ISA-compilation and linking) happens “JIT”.

Examples: .Net, Java, Python, V8 (JavaScript)