Data Types

A modern ISA understands several data types (implied by an instruction):

- Bits

- Bytes

- Ints (32 or 64 bits, whichever fits in a computation register)

- Short and long ints (16, 32, 64, 128 bits) not normally part of an ALU computation but supported in various instructions

- Pointers (i.e. addresses)

- Instructions

- Others: floats, strings, very long ints (currently 512 bits), vectors, …

Word

A word is a number of bytes that fits in a compute-register and on an ALU bus, which is often also the width of the data bus. Bytes and words can be fetched and stored in one instruction. Often other sizes can also be fetched and stored in a single instruction.

The order of bytes in a word, and therefore in memory, may differ between systems, though for obvious reasons they are the same in one system. Named after Gulliver’s travels they are called Little Endian (least significant byte has lowest address) and Big Endian.

CS experts must be aware of this possible difference to interpret memory dumps.

Addressing Modes

The CPU is connected to memory with an address bus, which is usually 16, 24 or 32 bits wide. If the bus is narrow, few addressable locations exist. To address more memory, it is sometimes split in a set of banks which can first be selected.

An ATmega microcontroller (computer-on-a-chip) uses the Harvard-model (alternative for von Neumann) in which program memory and data memory are separate. It has two 16-bit address buses. It addresses memory in 64K banks.

ISA instructions locate operands in different ways:

- register: the operand is contained in a register, e.g.

mv X0,X1 - immediate: the operand is contained in the instruction, e.g.

mv X0,#5 - direct: the operand is stored at a specific memory address, e.g.

mv X0,(#31357718) - indirect: the operand is stored at a memory address pointed to by a register, e.g.

mv X0,(X1) - indexed: the operand is an array element the index of which is stored in a register (base and offset can be immediate or in register), e.g.

mv X0,(X1+X2),mv X0,(X1+5),mv X0,(#12345+X2) - stack: the operand is located on a stack, e.g.

mv X0,(X1++)

All modes except immediate occur as source and destination. Often many modes are available for mv but fewer for ALU instructions.

Larger Structures

Two essential aggregate structures are

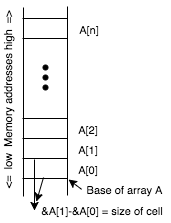

- An Array is a sequence of cells, each of which has the same type (bytes, words, pointers, …). Cells are accessed by computing the address of the first cell plus the size of a cell times the index (in the sequence) of the cell of interest. This means access time to an element is constant and independent of the array size.

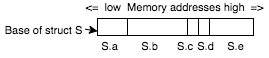

- A Struct is a collection of cells each of which has a different type (but the types are known beforehand by the program that uses them). Cells are accessed by computing the address of the first cell plus the sum of the sizes of the cells in between. Note that a compiler ‘knows’ the layout of a struct and computes all offsets beforehand. This means access time to a field is constant and independent of the struct size.

Arrays and structs are essential in all programming languages, though details may vary.

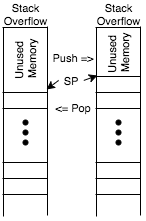

- A Stack is a structure which exhibits last-in-first-out behavior: the last element added is the first one taken out. At the ISA level it is implemented with an array and a pointer into that array. Adding an element means storing it and advancing the pointer. When the pointer reaches either end of the array, it’s called stack over/underflow. Unless prevented by bounds checking this is an error situation (hence the website). Typically recursion and function calls use a stack.

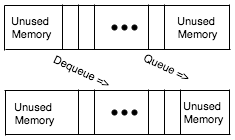

- A Queue is a structure which exhibits first-in-first-out (FIFO) behavior. It can be implemented using an array. Adding happens at one end just like in a stack, but removing happens at the other end. So there are two additional aspects:

- A second pointer is used to keep track of the removal point. When the two pointers meet there is over- or underflow (depending on the operation)

- When the insertion pointer meets the end of the array, it can be moved and insertions can continue (until the other pointer is met). The queue has two states: insertion above or below removal.

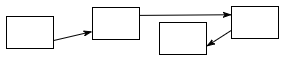

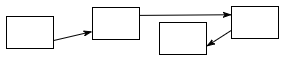

A Linked List is a set of structs each of which includes a pointer to another struct in the set (and other data). The order of structs in the list isn’t determined by their address but is encoded in the links. A linked list can easily exhibit FIFO and LIFO behavior, so they are used for stacks and queues when performance isn’t crucial.

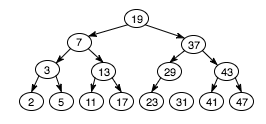

Many other pointer-based structures exist, optimized for different sorting and searching circumstances. For instance, using this binary search tree, we can determine set-inclusion of a number by following at most three pointers.

Memory Pyramid

We’ve seen two types of memory: registers and DRAM. Registers are faster (closer to the ALU) but require more transistors (more chip surface). DRAM is slower (separate chip) but offers more bang-per-buck (lower cost per bit).

System Engineering is about finding the perfect balance between cost and performance. This leads to the Memory Pyramid, with height indicating speed, and width indicating size.

- At the top are registers: incredibly fast but small in number because only so much can be placed next to the ALU. 100s of bytes, 1ns speed, $/byte

- Then there are caches: high-speed memory located in the CPU. MBytes, 3ns, $/Kbyte

- Then there is RAM: still relatively fast, and much larger. GBytes, 50ns, $/Mbyte

- Local secondary storage, much slower but comparatively huge in size

- Solid State Disk SSD. 100s GBytes, 100s ns, $/Gbyte

- Hard Disk HD. TBytes, µs, $/Tbyte

- Others (usually offline storage): tapes, laser disks, CD/DVD, etc.

1 Caches

A cache is a block of fast memory in which a copy of data from slower memory is kept in order to access that data faster. When the cache’s copy is altered, it is called dirty and it’s up to the caching system to copy that data back to slow memory.

When a CPU fetches an instruction, the chunk of memory which includes that instruction (called a page, typically 4K) is copied from memory to the cache. Since instructions are normally executed sequentially, the next instruction (or perhaps even the next several instructions) can then be read from the cache, saving time.

A Level 1 cache is located in a processor core (there can be more than one). Often there are two L1 caches in a core: one for data and one for instructions. A L2 cache is also located in each core, and holds both instructions and data. The L1 cache caches L2. Often there is also one L3 cache per CPU (i.e. shared by all cores).

Note that in a multi-core system L1 and L2 caches introduce an engineering challenge: a change by one core in its cache may invalidate another core’s cache. If a second core loads a memory page stored in one core’s cache, that page must be offloaded into an L3 cache.

2 Virtual Memory

The same principle is used to cache disk content in memory. This type of cache goes by the name Virtual Memory and will be discussed separately.