Data

Positional Number Systems

As mentioned: numbers are an abstraction. One number can be represented in many ways, including the positional number systems.

Earlier we have seen that binary numbers are useful because electronics can directly represent them and perform calculations upon them.

For humans, large strings of ones and zeros are confusing at best. Who knows at a glance the significance of 11000000101010000000000011111111?

For this reason humans use the decimal system with ten digits (originating from the fact that we have ten digits :-).

But still, long strings of digits aren’t our strength: the number above is 3232235775 in decimal. Who knows its significance?

In this case the number consists of 32 bits, but by convention we are used to writing it as four decimal numbers separated by dots with each representing an eight-bit (one byte) section: 192.168.0.254

For IPv4 this notation works, but it does have a disadvantage: each 8-bit section uses 1, 2 or 3 places in the decimal notation.

Hexadecimal

For this reason, hexadecimal is often used using the 16 digits 0-9 and A-F. Because 16 equals 2 ^ 2 ^ 2, a 4-bit number (which is called a nibble) can be written using one hexadecimal digit, and a byte as two digits.

Now, long numbers can be written in a way which humans can copy at a glance. For instance, the IP (v6) number of Google’s primary DNS server is: 2001:4860:4860::8888 (note: :: means all zeroes). Try it out in your browser: https://[2001:4860:4860::8888].

Other places where hexadecimal is used extensively include memory dumps. Memory is usually divided in bytes (8 bits) and then records (disk) or pages (memory) of 512, 1024 or 4096 bytes each (2^9, 2^10, 2^12). Memory addresses on a modern computer are typically 64 bits.

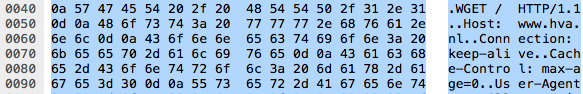

This screenshot is part of a Wireshark dump of an HTTP GET message for hva.nl. Most memory dumps look similar.

The left column consists of the offset within the package, the middle part shows the content in hexadecimal, and the right column the character interpretation (because humans read this more easily when it represents text).

Because memory dumps are hexadecimal, specialists using them must be able to convert hexadecimal to decimal to ascii almost on sight.

Hexadecimal to Decimal

One nibble: digits 0-9 are themselves; digits A-F or a-f => 10-15

One byte: 16 times the first nibble plus the second. E.g. f9 => 15*16+9=249

Larger numbers: per byte or nibble, and multiply each by a power of 16 (nibble) or 256 (byte). E.g. A4c9 = (10 * 16 + 4) * 256 + (12 * 16 + 9) = 42185

Such a calculation can be made using pen and paper.

Hexadecimal to Binary and Vice-Versa

One nibble: learn the table by heart.

0: 0000 4: 0100 8: 1000 12 C: 1100

1: 0001 5: 0101 9: 1001 13 D: 1101

2: 0010 6: 0110 10 A: 1010 14 E: 1110

3: 0011 7: 0111 11 B: 1011 15 F: 1111

Larger number: just string the digits together. A4c9 => 1010 0100 1100 1001

Similarly, the reverse is easy:

101 1100 1001 0100 1010: 5C94A

Decimal to Hexadecimal

If you are comfortable doing long division: repeated division by 16 noting down the remainders does the trick.

50109 / 16 = 3131 rest 13 (D)

3131 / 16 = 195 rest 11 (B)

195 / 16 = 12 rest 3

12 / 16 = 0 rest 12 (C)

50109 = 0xC3BD

If not, conversion to binary is easiest, noting down the nibble values using the table.

Two’s complement

One of the most effective System Engineering feats is two’s complement: a representation of negative integers which allows the same digital electronic circuit to perform addition of negative and non-negative integers as well as subtraction of those numbers!

Naively, negative integers might be represented by using one specific bit to represent the sign. For example, 00000101 might represent 5 (in one byte), and 10000101 might represent -5. There are two problems:

- Now there are two zeros: 00000000 and 10000000. Since zero is probably the most-used number, having to check which zero we’re looking at introduces significant overhead.

- addition and subtraction don’t work immediately 00000101+10000101=10001010 (-10) but should be 0. This means this representation requires different circuitry for addition and subtraction

In two’s complement a negative value is represented as the complement when subtracting it from the next larger power of two. So: for 8 bits the complement of a number n is 100000000-n (8 zero’s, nine bits). E.g. -5 is 100000000-101 is 11111011 is 0xFB.

In this representation the leftmost bit does indeed represent the sign 1 => negative, 0 => zero or positive. Also, there is only one zero: 00000000.

But most importantly, the rules for addition work whether a number is negative or positive:

11111011

00000101

--------8

00000000 (= zero in 8 bits, as it should be)

Conversion

Consider this 4-bit addition (we’ll use 4-bit numbers to keep the examples small):

1011 + 0101 = 0000

Is the first number positive (11) or is it negative (-5)?

You can’t tell!. The rules for addition are identical for positive and negative numbers, so the context decides how this should be interpreted.

In general data are just strings of bits; interpreting them without context is impossible.

We’ve explained how the two’s complement can be computed by the subtraction from the next power of two, but there is an easier way to do it:

- flip the bits (1 <=> 0)

- add one

So: 00000101 => 11111010 => 11111011

Interestingly, the other way round works exactly the same!

Other Data

What does the number 10111010101011011111000000001101 signify?

Information ≠ Data

It’s a trick question:, you can’t know. It’s just data, but without context it’s not information.

- It might be an IPv4 address: 186.173.240.13

- It might be a very large integer: 3131961357

- Or a negative integer: -1163005939

- It might be a very short text:

°-ð(degree symbol, minus sign, greek eth if it is marked up wrong) followed by a newline - Or it might be a memory pointer. Who knows what’s there.

- Further down we will see that binary numbers can also represent floating point (approximate real) numbers. This number is in fact -0.0013270393.

Would you believe this number (-0.0013270393) has several hits on Google?

It is a Microsoft error message indicating a corrupt heap; convert to hex to get the joke!

Floating Point Numbers

IEEE standard 754 is a standard for the representation of approximate real numbers:

- the largest numbers used in sciences (say the number of atoms in the universe)

- the smallest positive numbers used in sciences (say the weight of an electron)

- integers precisely (not approximately)

- common operators (addition, comparison) can be easily done in hardware

And we use only 32 bits for a number.

Scientific Notation

Humans are bad at long strings of numbers. What would you rather get: €1341265142643 or €924395963572?

Scientists have long known this and have come up with a notation which improves upon this

1341265142643 = 1.34 x 1000,000,000,000 = 1.34⋯ 10^12 = 1.34e12

This ‘scientific’ notation has two advantages

- Looking at the power of ten offers an immediate impression of the scale of the number (in the example above, 1.3e12 vs 9.2e11; the first number is bigger).

- As many digits can be shown as are useful given the circumstances.

In the notation 1.34e12 the number 1.34 is called the mantissa, and 12 the exponent. In calculators the number e is often used: 1.34e12.

Note that the exponent can be either positive or negative. 10^-3 = 1/(10^3) = 0.001. So 1.34e-2 = 0.0134

Calculation

Calculation is straightforward.

- In multiplication, the mantissas are multiplied while the exponents are added. 2e2 x 3e-3 = 6e-1

- In addition, the exponent should first be made the same and then the mantissas can be added: 1.2e4 + 2.2e2 =

- 120e2 + 2.2e2 = 122.2e2 or

- 1.2e4 + 0.022e4 = 1.222e4 or indeed

- 12e3 + .22e3 = 12.22e3

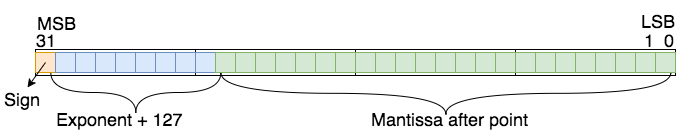

IEEE 754

The scientific notation is used as a basis in IEEE 754 with an obvious adaptation: since we are using binary numbers, the base for the exponent is 2.

Note that every binary number except zero contains a one (either before or after the decimal point). This implies that every number (except 0) can be normalized by shifting it left or right until it is written as 1.⋯. For example, the number 0.0000101, which is 5/128 can be written as 1.01e-5

Since the first digit of the normalized mantissa is always 1, it isn’t stored.

The exponent can be positive or negative. We could store it as a 2’s complement number, but in fact we simply offset it by 127. A typical engineering solution: this way sorting (the > operator) is the same for ints as it is for floats.

For instance the representation of 0.375 is

- it’s positive, so first bit 0

- 0.375 = 0.25 + 0.125 = 1/4 + 1/8 = 0.011 (bin) = 1.1e-2

- exponent bits 125 binary: 01111101

- mantissa bits: 100⋯0 (the first 0ne is dropped)

- 001111101100000⋯0

Conversion to Decimal

What floating point number does 0x40490fdb represent:

- binary: 01000000010010010000111111011011

- sign: positive

- exponent: 10000000 (128) - 127 => 1

- mantissa: 1.10010010000111111011011

- Note: working with fractions of 2 soon becomes error prone. An alternative is to view this as a large integer (convert to hex) and divide by 2^23. So: 1100 1001 0000 1111 1101 1011 = 0xc90fdb = 13176795.

ASCII

At their heart, computers process zeros and ones. But using positional numbers we can process all non-negative integers; using two’s complement we can process negative integers; and using the floating point representation we can process (near) real numbers. In short, we can process most ‘kinds’ of numbers.

But, for the moment skipping video and audio, there is another very important type of data we need to process: text.

The American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) is an ancient standard which plays an important role to this day. ASCII represents many common characters in numbers.

ASCII was created around 1960, in a time when the human-computer interface consisted of a teletype (which is a combined keyboard and printer). At the time, a 7 bit code was sufficient to represent all common letters (upper and lower-case), numbers, punctuation and necessary control codes to manage the teletype. For instance, ASCII still has a code to ring a bell in the teletype to get an operator’s attention when a message ends. Also, ASCII has a code for carriage return (the carriage is the small train that carries the printer head which hammers letters through an inked cloth ribbon) and for line-feed (which advances the scroll of paper to the next line). Whenever we embed a \n in a text to get a newline we are inserting a line-feed symbol.

Today we use Unicode to encode just about all known symbols, and we use encodings such as UTF-8 to pack unicode characters in single or double bytes. However, the ISO 646 subset of UTF-8 still coincides with ASCII and ASCII is still the preferred representation when we happen to be limited to plain text in the English alphabet.

The well prepared programmer can somewhat read (hexa)decimal data which represents text. Look up an ASCII table and you will see that there is logic to it. In hex:

- 00 and onwards are the control characters including NUL, BS, TAB, LF, CR and ESC

- 20 and onwards are the space and punctuation

- 30 and onwards are decimal digits

- 40 and onwards are @ and capital letters

- 60 and onwards are backquote and lower-case letters

Using this information you can decipher 49 20 41 4d 20 4E 4F 31